There are various recommendations how long one should not fly after surfacing from a dive. DAN has recently done a study where they did Doppler measurements on a plane and recommends an interval of 12 hours after a single dive and 24 hours after repetitive diving.

But one would think that it should be possible to use a decompression model that works well under water to compute such a time. So let’s do this in this post or at least compute a conservative estimate. To be specific, we will use the Buhlmann model. We do that calculation compartment by compartment and assume that when leaving the water, the tissue has the maximally allowed partial pressure for surfacing (i.e. this tissue was the guiding tissue for the final part of the ascent). Clearly, this is a conservative assumption. Then, according to the model

\(p_s = (p_i -a)b.\)Here, ps is the surface pressure and a and b are the usual Bühlmann coefficients.

Then we do a surface interval (whose length we wish to determine in the end) during which the partial pressure decays exponentially:

\(p_i(t) = f_{N_2} p_s+ (p_i(0) – f_{N_2}p_s)e^{-\gamma t}\)where f is the N2 fraction the the breathing gas (0.79 for air which we are probably breathing while waiting for the plane to board). Finally, we don’t want the cabin pressure to be less than the minimal ambient pressure that Dr. Bühlmann recommends. We want to parametrize the cabin pressure using the barometric formula which asserts (assuming constant temperature) that the pressure drops exponentially at height with decay constant that the pressure is 1/e at about hs=8500m above sea level. So, we set

\(e^{-h/hs} p_s= (p_i(t) -a)b.\)This we can then solve for t. Actually, being conservative, we want to throw in gradient factors. Again, being conservative, we don’t further linearly extrapolate gradient factors, but will use GFhi everywhere on the surface. Plugging everything in (with the help of Mathematica and some manual massaging) we find

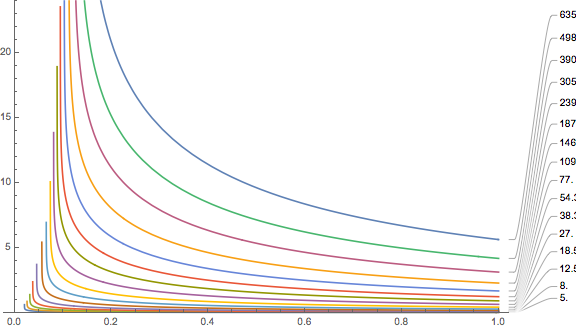

\(e^{\gamma t} = \frac{a GF/p_s + 1-f_{N_2} + GF(1/b -1)}{a GF/p_s – f_{N_2} +e^{-h/h_s}(1+GF(1/b-1))}.\)Now, we have to plug in numbers. For the cabin pressure, according to Wikipedia, we will assume h=2400m for older aircrafts. The wait times (in hours) for the different compartments are then shown in this plot:

You are supposed to see a number of things:

- The waiting time depends strongly on which tissue we are dealing with. For reasonably large gradient factors, only the tissues with half-times of several hours contribute significant waiting times. Remember, for this calculation, we assumed the loading is at its maximal value when you get out of the water. For realistic sports/tec-diving scenarios (as opposed to saturation diving) that should be quite hard even on a weeklong liveaboard with at least five dives a day. If slightly faster tissues are leading, the inferred no-fly times are much shorter, probably shorter than the queue at check-in. I looked at some data from real dive trips where people got everything out of their booked liveaboard but they got nowhere close to exciting the slow tissues. In the Subsurface planner I had to do five consecutive 2-hour dives with less than two hour surface interval to see at least some ceiling for the 239 minute compartment. In the plots, this has the blue line and leads to a no-fly time of much less than 5 hours.

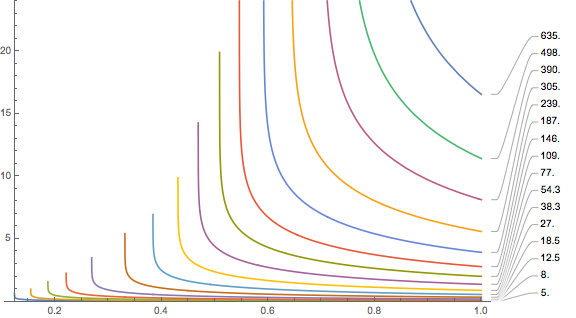

- The plot ends on the left (small gradient factors) with diverging values. These divergences move to higher gradient factors when you increase the cabin pressurisation equivalent altitude (for example by assuming a loss of cabin pressure, remember this is when the oxygen masks are supposed to drop from the ceiling)

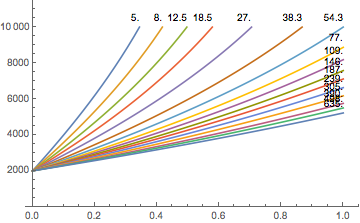

Same plot with 4500m of altitude This comes about as the no-fly time becomes infinite or even complex as according to the Bühlmann-with-gradient-factors limit, your are not allowed to be at the ambient pressure at that altitude even when saturated with the nitrogen that you experience at sea level. We can compute this limiting altitude by solving

\(f_{N_2} p_s = e^{-h/h_s} p_s (GF/b-GF +1) + a GF /p_s\)

for the altitude via

\(e^{-h/h_s} = \frac{f- aGF/p_s}{GF/b -GF +1}.\)

This is shown here, the maximum altitude after waiting an infinite amount of time:

Maximal altitudes in meters for the different compartments as a function of the gradient factor. - All these calculations are for air (or nitrox underwater since all we used was the assumption that the nitrogen saturation is at the limit). In particular, in view of an earlier post (N2 vs. He, what’s the difference?) there should not be large differences.

- You could try to repeat the same argument for VPM-B but according to that model, if you followed it during the ascent, the no fly time would always be infinite: The ascent is determined such that when you surface and stay at ambient pressure, you will just create the maximum amount of free gas that is barely allowed. So going to any altitude and lowering the ambient pressure further would release more free gas than allowed, no matter how long you waited. The only way out would be to produce fewer bubbles on the earlier ascent while still in the water, then you would have some reserves to go to altitude.

What are we supposed to conclude from this? One takeaway message is waiting for the recommended 24 hours is not totally off, in particular if there is a chance that your very slow tissues have loaded a significant amount of nitrogen.

On the other hand, for realistic dives, 24 hours is likely on the very conservative side. At least from the perspective of decompression theory. From this perspective it is a total mystery to my what kind of reasoning dive computers use to determine a no-fly time.

Apart from these model considerations, DCS symptoms often enough do not show up immediately after a dive but up to several hours later. And when you are in that situation that you find yourself with DCS symptoms (even those that would have occurred irrespective of flying or not) your chances for immediate proper treatment are probably much higher if you are not confined to an aircraft above the middle of the ocean. So even from that perspective it makes sense to wait a bit more to make sure you will not need a chamber in the next few hours.

PS: If you want to play around with the formulas, here is my Mathematica notebook.

Hi,

I’d like to see the effect of breathing O2 at the surface on the no-fly time (NFT).

Would it be possible to start with a substantial dive (say: 20min@40m) to preload the compartments and then calculate the NFT for different scenarios?

First would be 21% O2 (= plain air) for reference, then some steps like

10 minutes of 100% O2,

20 minutes of 100% O2,

30 minutes … ,

up to 4 hours (that probably requires a large O2 tank)?

Some sources state that they have had no adverse effects using a 1:4 ratio, so that every 1 minute of O2 would cut 4 minutes off the NFT (starting with 24h).

My mathematica knowledge is “I believe it is a modelling program with mathematics included”, so that isn’t the swiftest way to go for me.

Would it be possible to add the NFT to subsurface? I tried to fake it with a dive at altitude and some superextended deco stop @3m on O2, no conclusive result so far.

Kind regards

André

Of course it would be possible to add this calculation to Subsurface. But the resulting no-fly times (assuming not too extreme dives where deco is typically determined by the faster tissues, would be radically shorter than what is suggested by the agencies like DAN. As a rule of thumb, you could probably say that in the first plot you can ignore all tissues with half times longer than the dive time (but careful with multi dives per day for several days, there you might be able to also load slower tissues). I would not feel to good with providing a program that says “no fly time 90min” when DAN says, you should better wait 24h. I don’t want to be the person that fingers are pointing to when blame is to be shared when it comes to a complication on a flight. That said, my personal feeling is that either there is another relevant process that is not captured by the traditional tissue loading models or the agencies’ recommendations have quite a lot conservatism built in.

Regarding breathing O2 at the surface: That would indeed lead to much faster off-gassing (as the nitrogen gradient between tissue and breathing gas is about 0.8bar lower) but the amount of time saved once more depend on which tissue is controlling the limit. To see the effect in the mathematica notebook, in the assignment to “values”, replace the f-> 0.79 by f->0.

I know this is an old post but I have performed No Fly Time calculations in my own decompression/log book software and tested the impact of breathing O2 at the surface (theoretical).

I compute no fly times using gradient factors just like you do for surfacing from decompression dives and target a 35% gradient factor at 10,000ft altitude. (No real basis for the 35% GF just seemed reasonable)

Next you look at your last dive, put in a gas switch to O2 at zero ft at the end of the dive and add another segment 30 minutes later still on O2. That will off-gas at the surface using oxygen for 30 minutes. It has a radical impact on time-to-fly computation.

For example – with a surfacing gradient factor of 17 in tissue compartment 4 the computed time to fly was reduced from 6:37 to 0:00 by using 100% surface O2 for 30 minutes. This also achieved total desaturation of all tissues in under 2 hrs.

I am not recommending that you do this is practice – it is just a theoretical calculation.

For an approximate 100′ drive of 25 minutes total run time on air you have a surfacing gradient factor of about 65 in tissue compartment 4.

The computed no-fly time using my parameters above is 5:33 and desaturation time is 12:35

With 15 minutes of O2 at the surface NFT goes down to 1:35 and desaturation time is 8:50

With 30 minutes of O2 at the surface NFT goes down to zero and desaturation time is 4:38

I still think, it is not tissue loadings that determine the no fly time (like they determine deco schedules). But your suggestion makes for an interesting experiment that could be performed as a double blind study: Let divers do a dive (with some significant gas load on the way). At the surface, let them breath a gas (some of them breath air, the others oxygen) for say 30min. Then let them board a flight. Are there significantly more reported problems amongst those that used air at the surface compared to those that had oxygen?